I saw his son before I ever met him, Shaukat Sheikh, Irshad was making some phone calls in and NGO office and I saw the MISSING poster on the desk, held it out against him and took some photos. We were at Ambojwadi, embroiled in Ganpatpatil Nagar, far, far, far from other concerns.

The second time I ran into Shaukat, I was smoking a cigarette outside Irshad and Shafi Law’s office in Antop Hill, I don’t recall why I was there- it was becoming a bit tiresome when they’d call me all the way out for 5 minutes of information and I’d end up staying the entire day.

I recognized him immediately, even in the dark gulley. His tall, emaciated frame and that hawkish face; those alert, shining eyes. I’d photographed him at his home a few weeks ago in Golibar, Santacruz to cover the disappearance of his son in a Slum Rehabilitation Authority (SRA) fraud.

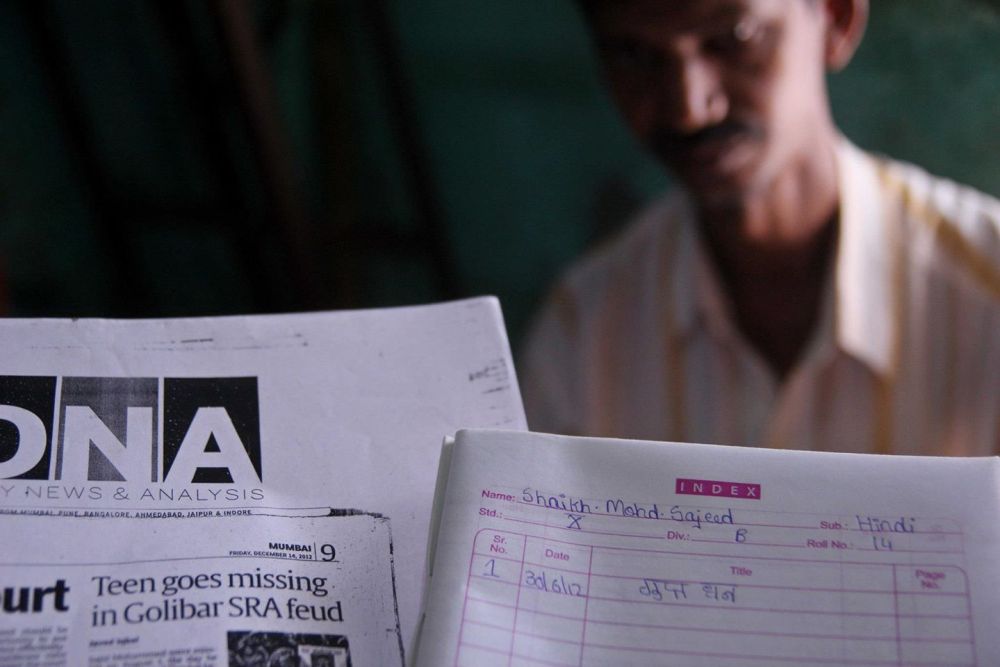

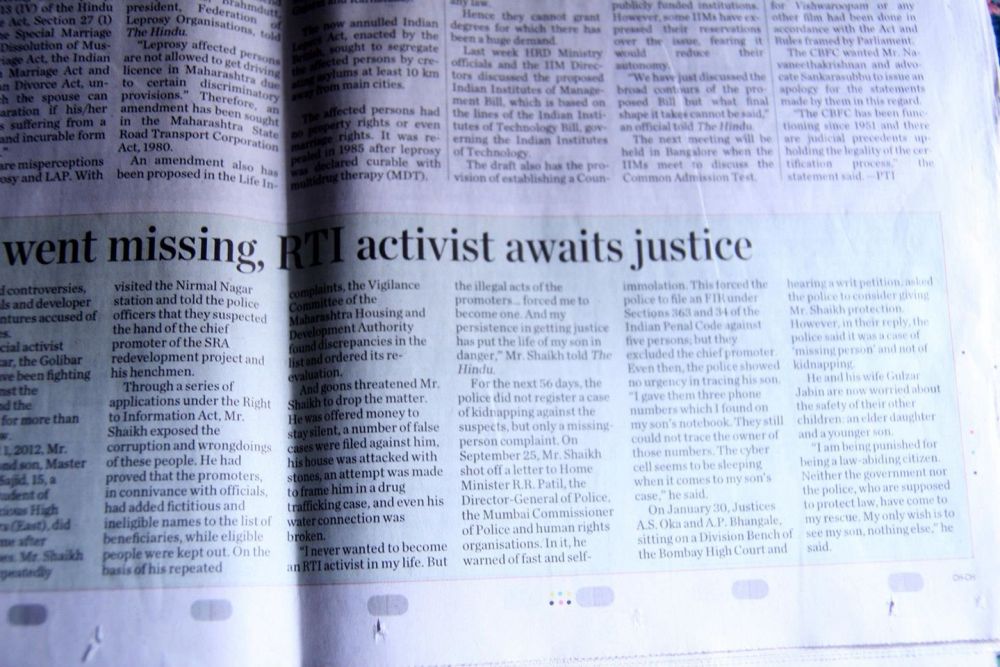

Shaukat was passed over for relocation when his area was allocated for redevelopment by a building agency, Shivalik Ventures, on the basis of an SRA criteria that allows free housing to slum-dwellers that have resided in their respective area since 1995. However, several others that did not meet the criteria were allocated housing, a fact Shaukat attributes to forgery and corruption, instigated not by the residents, but the promoters of Shivalik’s agenda in the slum.

Amid threats to life and family, he launched a series of RTIs (Right to Information query) into the builder’s practice, and it was revealed that the promoters had added fictitious names to the list of beneficiaries which forced a re-evaluation of the list by the Vigilance Committee of the Maharashtra Housing and Development Authority.

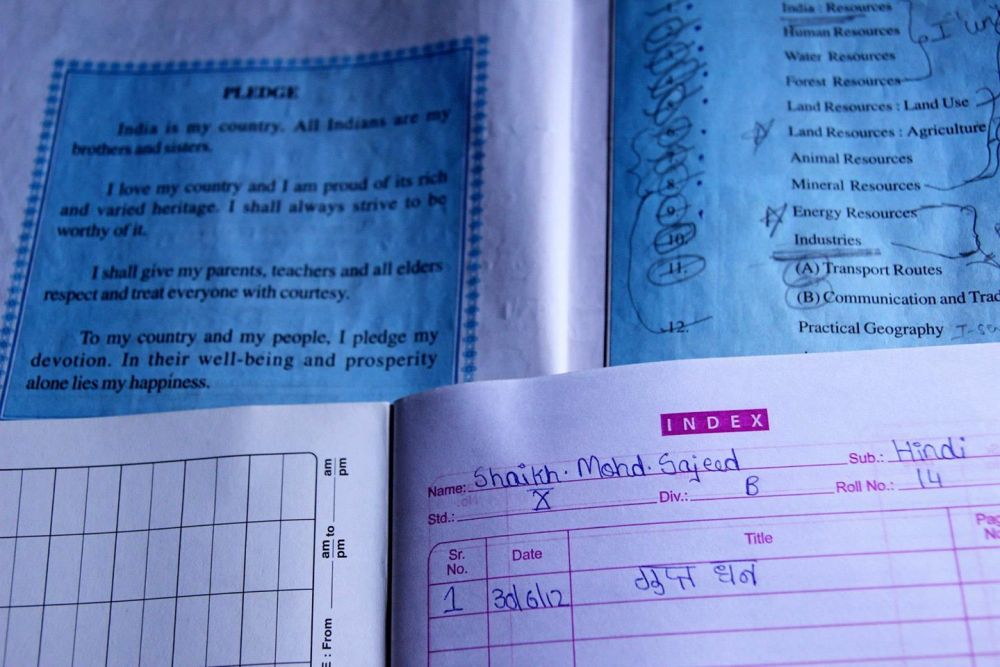

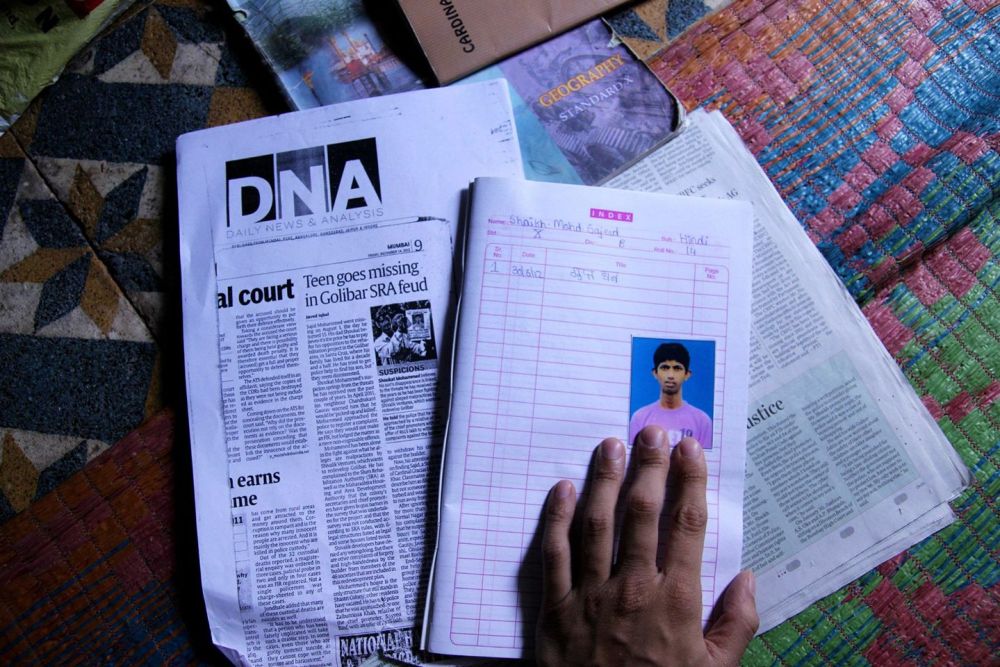

On August 1, 2012, Mohammad Sajid, Shaukat Sheikh ’s oldest son disappeared on the way back from coaching classes. It was his fifteenth birthday.

It took 2 months for the police to recognize the case as a kidnapping, though fouler play is suspected still. I remember asking Shaukat if he thought the investigations of the police, the formation of a special investigation team on the order of the High Court, could possibly result in the return of his son. He told me at this point he’d rather just know what had happened to him.

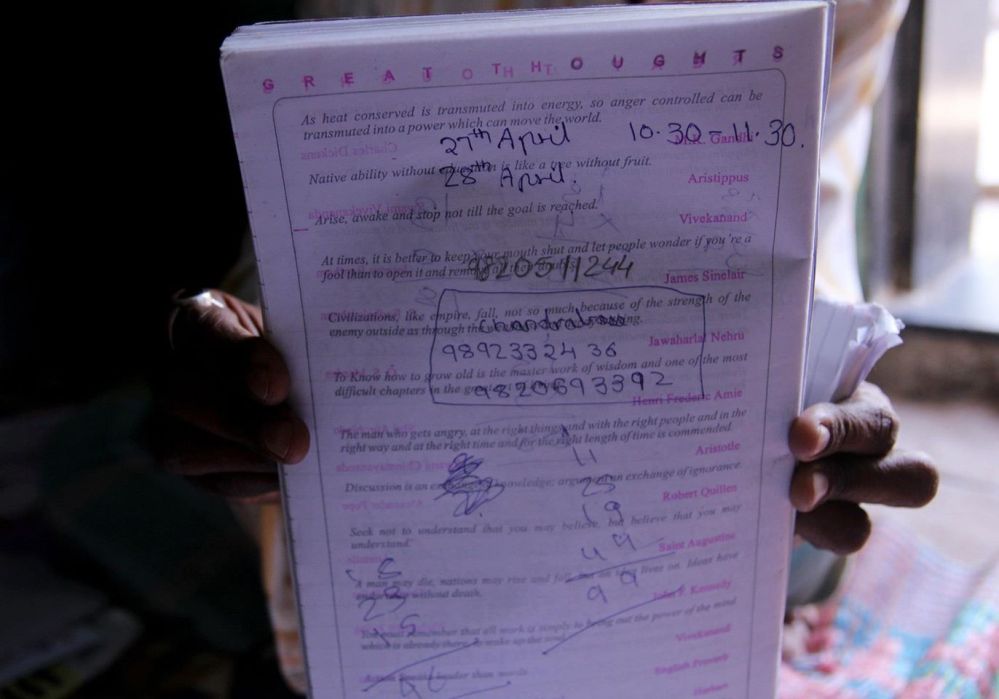

A mysterious phone number showed up in three of Sajid’s school books. Sajid didn’t have a mobile phone. None of his friends had mobile numbers. Was this a relevant fact? The police refused to investigate the number, highly unusual given the context. Shaukat’s own digging revealed little.

There, in Antop Hill, he was visiting Shafi and Irshad to tell them of his court hearing the next day, where he expected the judge to put a deadline to the stagnant police investigation. He asked me if I could make it to the High Court the next day, I promised I would.

Shaukat is a simple person, who smiles kindly at jest. His lawyer, Wesley, a pro bono Human Rights guy, is joking with him, trying to work off his nerves before they enter the courtroom. He tells us all to turn our phones off; he asks me to button my collar, as it would be more formal. I oblige. He tells them not to speak, and let him handle it with the judge. I strike a conversation with his assistant, a dreamy eyed law school undergraduate. We’ll talk about noodle wrapped chicken at Mohammad Ali road. We enter.

This is a maritime courtroom, I just climbed onto a deck. Other than the light streaming in from the high windows on the upper level, the large room is lit simply by overhead lamps hanging from the clean, painted aluminum ceiling. Some cops stand around, they all wear shoes of the same ugly tan orange leather. There is the spirit of assembly, we’re all waiting for the judge to arrive; Shaukat is sitting a few spaces to my left on one of three benches on the dock, his wife to my side and Wesley, the lawyer, hovers behind him reviewing his notes.

The stacks of paper the court clerks handle on the long desk are voluminous. It appears to be pretend order, many steps to a dance of no tune. I’ve seen it in other government offices- stacks of damp, age old documents decaying in towers- they look like they haven’t been touched since being put there, and it’s difficult to imagine they would serve any purpose in the condition that they are. Metric tonnes of never digitized records that no one can handle now without tearing from cover to cover at the slightest touch. It’s all information they never knew how to process anyway- funny how they always want more.

The judge enters, preceded by a couple of bailiffs in cute red turbans, and court begins.

About half an hour into it, Shaukat turns to me and signals ‘2’. His case number is 8, there appear to be 2 left. Before I know it, it’s time.

I thought he’d lost his nerve in front of the judge, a sharp faced, fair skinned man with perfect English and an authoritative voice, but really he seems to be working himself into a respectful, subdued insistence that works really well on the judge. The main conflict here with the defendant is the reluctance to acknowledge the case as a kidnapping. The judge gives the police a week to conclude their investigation and orders immediate police protection for Shaukat and his remaining family- a 24 hour 2 man detail. Shaukat’s wife’s phone goes off. It’s a half minute of terrifying nonchalance until she realizes it’s her’s and rushes out of the room, ushered by annoyed but sympathetic court clerks and cops.

The judge is inquiring the cause of the delay in the results of the investigation, the state appointed defendant isn’t being convincing.

Does Shaukat understand what’s going on? Wesley is beaming.

It’s done, we exit the courtroom. In the busy hall, we clutch a corner against a bannister, one of the many that seem to be holding the place up and huddle around Wesley as he explains the verdict, telling Shaukat about the protection detail and the deadline. Shaukat asks if they’ve recognized the case as a kidnapping. They haven’t. Wesley explains that the court will await the police report. Shaukat, no one present, has any faith in the police.

What’s that look on Shaukat’s face? A crumbling look. Placcant. Complicated. I’ve seen it before, at school when a child would be told what they could not do, without hope or the possibility of reasoning or dialogue. A worthless affront by a system that doesn’t care; it surprises and frightens me to see that as it was for us as children, it will be for us as men, led unquestioningly by a useless cavalcade of better dressed, better educated fools.

Shaukat stood up against oppression and they took his son away. He turned to the system for help, the system that had betrayed him in the first place and it did nothing. Now, years later, it appears that the court will grant Shaukat recognition for his persistence. Acknowledgment of his loss? No, not yet. And no justice either, perhaps never that.